An overview of hacking LTE

This document serves as a starting point for individuals looking into hacking cellular network technology, in particular Long-Term Evolution (LTE). It will provide an overview of the currently known vulnerabilities and methods of breaking cellular security.

What is LTE?

Defining the various mobile telecommunication standards can be quite confusing. For each generation international committees agree on improvements the new generation shall have over the previous one. So far there has been commercial releases of 1G, 2G, 3G and 4G technology with 5G being the next generation currently in development. A cellular network generation like 4G is a detailed set of standards and capabilities that a system has to have in order for it be able to called 4G. LTE is a an example of such a system that was developed and submitted as a candidate for a 4G wireless service. However, confusingly, normal LTE doesn’t actually meet the technical criteria of 4G so it is sometimes called 3.95G, which led to the development of LTE Advanced which is a major improvement of LTE and actually meets the standards of 4G.

What’s important to remember is that LTE is an implementation of the 4G standards and that 4G LTE is the de-facto technology used by carriers across the world. If you’re interested in learning more about the history of cellular network generations I recommend reading the paper From 1G to 5G, What Next?

How Does LTE work?

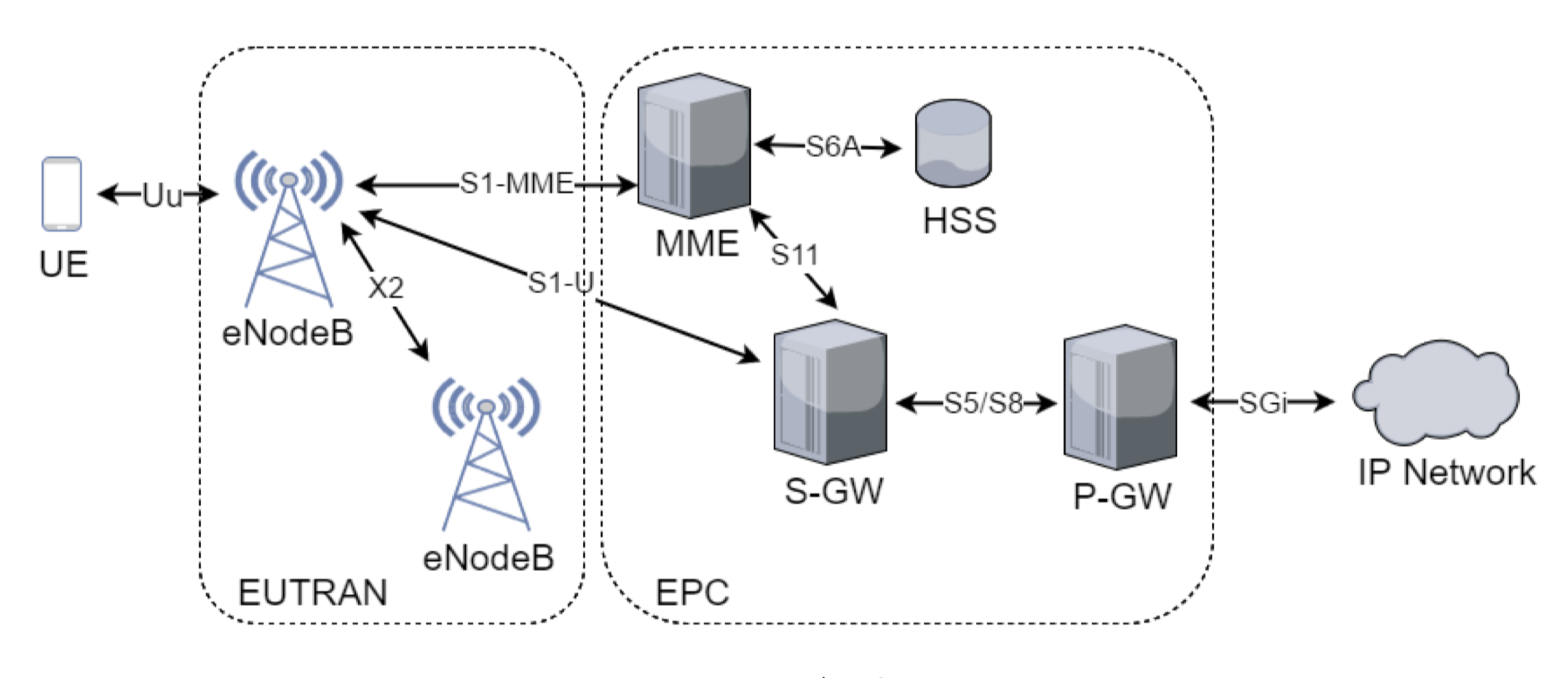

The LTE network architecture is made up of three clearly defined parts. Firstly are the end-point devices such as your mobile phone which are known as User Equipment (UE). The second are the intermediate connectors which are the base stations (eNobeB) that act as the first point of contact between a UE and the wider network, this is known as the Evolved Universal Terrestrial Radio Access Network (EUTRAN). The final part is the core which routes packets through the network as well as authenticating and managing a user session and many other tasks. This is known as the Evolved Packet Core (EPC). There are many subcomponents in a LTE network. Below is a diagram illustrating an overview of the network and a brief explanation of each component.

- UE (User Equipment): the user’s device which contains the Subscriber Identity Module (SIM or USIM). This is where the IMSI number used to authenticate a user is and the special key used to encrypt traffic is kept.

- eNodeB (evolved NobeB): the base station that communicates with the UEs and carrier’s wider network.

- MME (Mobile Management Entity): responsible for authentication and management of UEs in the network.

- HSS (Home Subscriber Server): stores the security parameters such as keys of the UEs.

- S-GW (Serving Gateway): a communication point between EUTRAN and the EPC.

- P-GW (PDN Gateway): a routing point between the carrier’s network and the wider packet data network.

The above diagram comes from the paper Easy 4G/LTE IMSI Catchers for Non-Programmers which explains in greater detail the infrastructure of LTE. For an in depth analysis 4G: LTE/LTE-Advanced for Mobile Broadband is the go-to book on the subject of LTE. It’s written by engineers at Ericsson who were part of the development of the technology - be aware it gets into the nitty gritty of the communication protocols and speaks about wireless networking at an advanced level.

LTE Security

LTE has security built into its underlying design and as a result there are lots of steps taken to ensure the confidentiality, integrity and authenticity of your mobile communication.

The main overview from the point of view of the user is that LTE uses a hardware protected 128 bit key called K which is used to derive security parameters and more session keys. K is stored inside of the UE’s SIM and in the carrier’s core network - it never leaves those two locations and is never transmitted in its lifetime. There is a complex key hierarchy where essentially every step of communication and sometimes even every protocol has its own key, for example between an eNobeB and a MME.

In order for a device to authenticate itself to the network a UE exchanges specific hardware tokens with the core to identify itself. The main token that is used is the International Mobile Subscriber Identity (IMSI) number, this is explained in further detail in the IMSI Catchers section below.

I highly recommend watching this talk below as it is a great introduction to LTE security, it’s not too long and is easy to watch.

Types of Attacks

IMSI Catchers

Despite the high level of encryption in LTE there are still a number of packets that are exchanged unencrypted between a UE and an eNodeB in the initial phases of communication. These packets that are sent are to do with authenticating the UE to the network so that that the EPC knows who it’s communicating with. These packets are sent as plaintext as there isn’t the ability to encrypt them since the EPC doesn’t know who its talking to and therefore which keys to use. The 64 bit IMSI number is one of these pieces of data. The IMSI is only ever sent the very first time a mobile device attempts to connect to a brand new network, otherwise if it is connecting to a network it has communicated with previously it can use something known as a TMSI (a temporary and less critical version of the IMSI). An IMSI catcher exploits this aspect of LTE by listening for that first transition of an IMSI number by the UE. The dangers this poses are that they could be used to identify an individual or individuals through their device’s unique IMSI. This could be then used to physically locate a target or perform mass surveillance on a group of people in a geographical area. This is why IMSI catchers are often associated with governmental organisations as a method of surveilling targets. Read more about this here.

The basic steps of performing an IMSI Catcher attack are to mimic a genuine eNodeB cell tower and to get your targets to connect to it. Due to the fact that a LTE device will always connect to the network cell with the strongest signal you can quite easily guarantee your target device will communicate with your cell tower, especially in a controlled lab environment. Once the IMSI catcher begins communication with a mobile device it will force the UE to disclose its IMSI number as the fake cell tower represents a new network that the UE has not communicated with before. Mimicking a cell tower requires specific hardware that ranges in price from a few hundred dollars to a few thousand depending on what you’re objectives are. The hardware that is used by an attacker attempting to target people in a real world setting will differ greatly from someone in a lab environment who wants to analyse LTE traffic. An example of a LTE eNobeB lab kit you can buy is this which costs about $6,000.

There is a large amount of documentation on creating your own IMSI catcher. The best papers I found were: Easy 4G/LTE IMSI Catchers for Non-Programmers and Practical Attacks Against Privacy and Availability in 4G/LTE Mobile Communication Systems.

Denial Of Service

There are a number of ways of performing LTE denial of service attacks. Jamming is one technique all wireless communication is particularly vulnerable to. This is where the attacker employs hardware that transmits signals at the same frequency of the communication in order to cause disruptions. There are a number of publications showing that one can quite easily jam LTE signals with low cost off-the-shelf equipment. The publication Jamming LTE Signals goes into depth on this topic.

A more nuanced way of launching denial of service attacks again involves creating a fake base station that your victim connects to. This means that you are in control of the point of entry of the UE into the network and therefore can stop all communication or even specifically deny certain services or types of communication. This is discussed in the previously mentioned publications LTE security, protocol exploits and location tracking experimentation with low-cost software radio and Practical Attacks Against Privacy and Availability in 4G/LTE Mobile Communication Systems.

DNS Spoofing

On the data link layer of LTE user data sent between the UE and the eNodeB is encrypted but it is not integrity protected. This means that a message payload could be modified by a rogue base station without any flags being raised. This lack of integrity protection in the data link layer is the centre point of the publication Breaking LTE on Layer 2. The paper details how an attacker could observe a user’s traffic and using packet fingerprinting figure out when a DNS query is made and alter the response to direct the victim to a malicious HTTP server. One of the author’s of the paper gives an informative and concise presentation on their findings in the video below.

Eavesdropping Attacks

There doesn’t exist a published method that allows an attacker to see the user data sent over a 4G LTE connection. Due to the fact that LTE uses symmetric key encryption with a 128 bit key that is never transmitted outside of the two endpoints, it does not appear possible to observe the data packets (such as phone calls, text messages etc.) of a victim.

However there still may be value in performing eavesdropping attacks on a LTE target depending on what your objectives are. As explained above, in DNS spoofing and ISMI Catchers, a MiTM LTE between the base station and the UE permits an attacker to perform a number of nefarious tasks. Another strategy for a MiTM LTE attack is a downgrade attack. As you may have noticed when travelling through less populated, less developed areas your mobile phone may switch to a lower mobile communication standard. Your phone will switch to a lower standard if it is the only viable option it has. This fact can be taken advantage of by attackers who wish to perform a number of nefarious tasks such as leak location, leak user identity and even potentially snoop on your traffic. For example an attacker could force your LTE device to use the older Global System for Mobile Communications (GSM). Despite having been designed with security in mind GSM is vulnerable to many types of attacks and the cryptographic algorithms (A5/1 and A5/2) used to encrypt user data are breakable (read more about the vulnerabilities in GSM security here). The way to execute a downgrade attack is similar to IMSI catchers in that you create a fake base station that you force your victim to connect to. Once they have connected and you have forced the device to communicate using a lower mobile communication standard, breaking the encryption should be trivial. A detailed guide on how to this is described in the paper LTE security, protocol exploits and location tracking experimentation with low-cost software radio.

There is also off-the-shelf equipment that allows one to observe and analyse nearby encrypted LTE traffic. One such product is the SRS LTE Air Interface Analyzer which allows the user to “capture all downlink traffic in any LTE cell in any frequency band”.

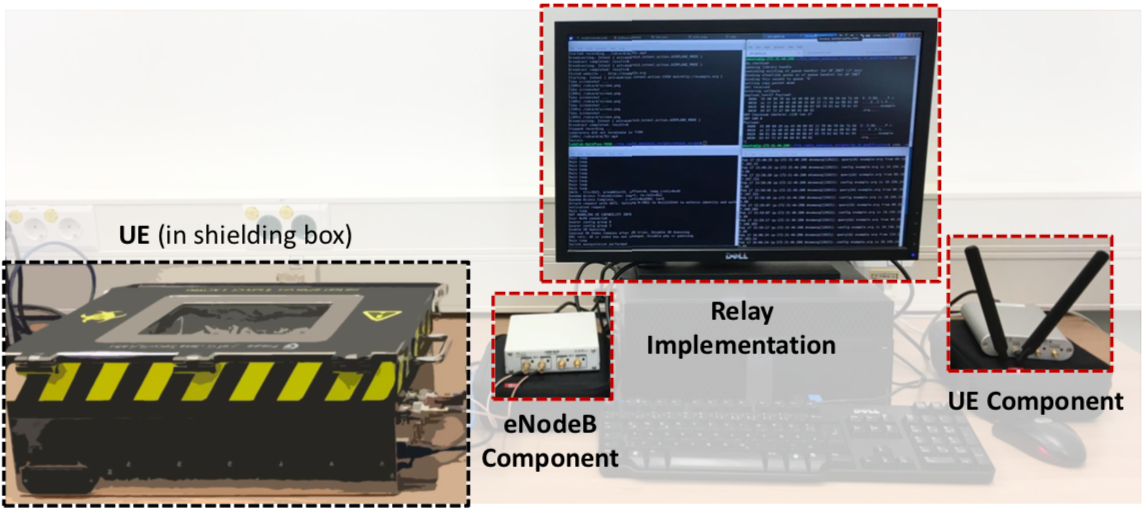

Software Defined Radios

One topic you will come across if you are considering building your own rogue base station are LTE Software Defined Radios (SDR). A SDR is a wireless communication system where certain components that are normally implemented in hardware are instead implemented in software. This allows individuals to recreate LTE components using their personal computers. srsLTE is free and open source code that allows a user to recreate an eNodeB base station that fully implements LTE communication standards using a computer and some basic wireless hardware. Below is a picture from the paper Breaking LTE on Layer 2 that shows a setup that uses two srsLTE SDRs to create a lab LTE network. The first SDR emulates an eNodeB towards the UE, and the second SDR emulates the UE towards to commercial network.

References and Recommended Reading

There are a lot of interesting resources on the Internet regarding LTE hacking.

3GPP is the actual organisation that develops most of the mobile communication protocols we use, including LTE and LTE Advanced. Their website contains lots of documentation on their work. I recommend having a look around there in particular the specifications on “Security Algorithms” and “Security Aspects”. However be aware these are technical documents and therefore very dry reads, worth having a look at though.

There is some cool work being done working to protect against LTE attacks. Seaglass is a project conducted by researchers from the University of Washington in order to find IMSI catchers across a city. The paper IMSI-Catch Me If You Can: IMSI-Catcher-Catchers is similar and shows in detail how to detect “artifacts in the mobile network produced by IMSI catchers”.

Here is a list of all the academic publications I have referenced:

- From 1G to 5G, What Next?

- Easy 4G/LTE IMSI Catchers for Non-Programmers

- Practical Attacks Against Privacy and Availability in 4G/LTE Mobile Communication Systems

- LTE security, protocol exploits and location tracking experimentation with low-cost software radio

- Jamming LTE Signals

- Breaking LTE on Layer 2